Patient Resources

Get Healthy!

Mouse Study Points to Possible Breakthrough Against Spinal Cord Injury

- November 12, 2021

- Dennis Thompson

- HealthDay Reporter

Severe spinal cord injuries are incurable today in humans, but a new injectable therapy that restored motion in laboratory mice could pave the way for healing paralyzed people.

The therapy -- liquid nanofibers that gel around the damaged spinal cord like a soothing blanket -- produces chemical signals that promote healing and reduce scarring, researchers report.

The treatment produced astonishing results in lab mice paralyzed by spinal cord injuries, according to senior researcher Samuel Stupp, founding director of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill.

"We found that in about four weeks effectively, somewhere between three and four weeks after injection of the therapy, the paralysis was completely reversed and the mice are able to walk almost normally," he said.

The researchers plan to take their findings to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration next year and apply for human clinical trials, Stupp said.

If effective in humans, the nanofiber therapy could solve a persistent medical challenge -- restoring movement to a person paralyzed by a spinal cord injury.

Damage is tough to reverse

Nearly 300,000 Americans live with a spinal cord injury today, the researchers said in background notes. Less than 3% with complete injury ever recover basic physical functions.

Surgeons do their best to stabilize the spine and repair damage around the spinal cord caused by a car crash, sports accident, gunshot wound, explosion or some other traumatic event, said Dr. Jeremy Steinberger, director of minimally invasive spine surgery for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

But there's nothing doctors can do right now to directly promote healing of the spinal cord.

"A lot of the time the damage is done and, sometimes, despite a great surgery and a scan that looks good, the patient doesn't have any improvement," said Steinberger, who reviewed the findings. "It's a very frustrating thing as a surgeon to see that we do everything we can but we still have patients who can be vent-dependent, paralyzed, loss of bladder and bowel."

Study leader Stupp elaborates on the new findings in this video from Northwestern:

The idea behind this new therapy is that as surgeons are repairing damage to the bones of the spine, they inject the nanofiber liquid into the area surrounding the injured spinal cord.

The nanofibers "measure about 10 nanometers in diameter. A 1-nanometer filament would be like taking a human hair and dividing it 100,000 times," Stupp explained.

"The tiny fibers that are in the liquid, when you inject them, as soon as they touch the living tissue of the cord, the tiny fibers make a network of fibers, like a mesh of fibers," Stupp continued. "This mesh resembles the natural environment that cells have in the spinal cord. It's the same architecture. It mimics the natural tissue."

The fibers then send signals to cells that promote the regeneration of nerves as well as growth of blood vessels and other structures needed to support spinal cord recovery, the researchers reported.

The nanofiber mesh also vibrates to mimic the motion of natural chemicals in the body, making them better able to communicate with cells and promote healing.

"If they are moving very quickly, they are remarkably effective as a therapy," Stupp said. "When we slow down the motions of the molecules, the therapy is not as effective. This is something that has never been observed."

The nanofibers are made of peptides, the building blocks of proteins, and they naturally dissolve within 12 weeks without noticeable side effects, he said.

"The therapy is very safe because it's made of up natural things," Stupp said. "The therapy biodegrades completely into nutrients. It disappears completely into nutrients that feed the cells."

'Very little scarring'

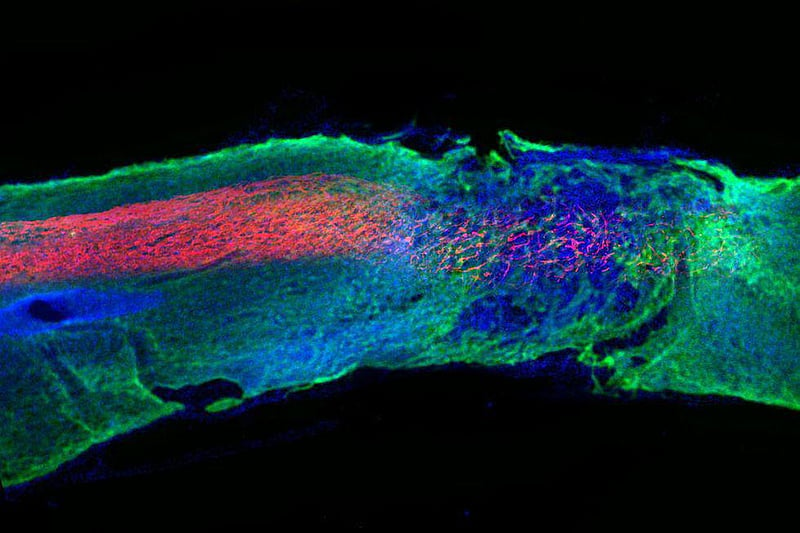

Examining the healed mice, the investigators found that the ends of severed nerves (called axons) had regenerated, and the natural insulation that protects nerves had reformed around them.

The nanofibers also significantly diminished the amount of scar tissue that formed at the injury site, and caused new blood vessels to form and feed the recovering tissues.

"The scar is actually what causes permanent paralysis. Even though the neurons are still alive at the site where they were severed, the body produces this scar, which is a physical barrier. The axons cannot regenerate because they have a big hard scar in front of them," Stupp said. "In our therapy, there was very little scar formed. That facilitates the regeneration of the axons."

Steinberger said he's excited by this research, but urges folks not to become too enthusiastic until human trial results are available.

"It sounds like there is a ton of potential. I think we have to be guarded in our optimism, because when it works in mice, it doesn't always carry over to success in human trials, but I'm excited to see what happens," Steinberger said. "It's a brilliant concept."

The findings were published Nov. 12 in the journal Science.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has more about spinal cord injury.

SOURCES: Samuel Stupp, PhD, founding director, Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.; Jeremy Steinberger, MD, assistant professor, neurosurgery, orthopedics and rehabilitation medicine, and director, minimally invasive spine surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City; Science, Nov. 12, 2021